From the archives: ten classic perfumes

Hello! Welcome to the newly refurbished site. All the posts on the perfumes in Coming to My Senses are in one place now, the new book page has all kinds of fun extras on it, and I hope you’ll find the old blog posts much easier to browse. To celebrate, here’s a little something from my archives that never made it on to the blog. A couple years ago Harper’s Bazaar asked me to name the “ten most classic perfumes.” Since they only pulled a few quotes from what I sent them (this happens a lot) I thought it might be fun to post the original.

* * * * *

When Harper’s Bazaar asked me to make a list of the top ten “most classic” perfumes I pictured an overcrowded life boat: who would be rescued, and who would be thrown to the sharks? Below, in no particular order, are ten iconic perfumes that show up in movies, books, music and art. They’ve spawned many imitators, continue to inspire perfumers, and women have worn them happily for decades. Beyond that, we’ll have to argue amongst ourselves.

Note: I excluded some truly great perfumes because they have been discontinued, are very difficult to find, or have been reformulated so radically that they are unrecognizable. Though the perfume industry prefers not to admit it, most perfume formulas are tweaked over time to account for changes in materials and taste–the older the perfume, the more the tweaks.

Patou–Joy (1929)

Released on the eve of the Great Depression, Joy is about luxury and abundance. Its opening smells like money dressed for the opera. But in twenty minutes the flowers begin to tumble out–roses and jasmine and jasmine and roses and more jasmine and roses as if there could never be too much of a good thing. Joy has lost some of the dark growl in her base over the years, and her flowers have thinned a bit but she is still a grande dame.

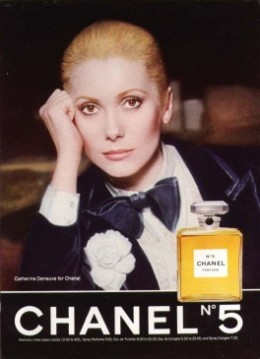

When it was released, Chanel No. 5 was the height of cool modernity. It has since become an indomitable pop icon. I sometimes think Chanel could put rancid hairspray in that instantly recognizable bottle and it would continue to sell like crazy. Thankfully, they have treated their great lady with respect, and her massive dose of aldehydes still give her an ageless, polished presence. No. 5’s influence can also be felt in Estee Lauder’s contemporary classic White Linen, and in 2007, Chanel released, Chanel Eau Premiere, a sunny younger sister of No. 5.

Chanel–No. 19 (1971)

Before “fresh” in perfume meant the aromachemical calone (think Acqua di Gio, Cool Water, L’Eau d’Issey Miyake and most of the 90’s) or the white musks of laundry detergent (pretty much every contemporary perfume going), it meant the green slap of galbanum and the cool, powdery touch of iris. No. 19 has both of these along with a tender heart of rose. It is a perfumer’s perfume, admired for its balance and construction. It has suffered through some changes, and become harder to find, but is still very much worth seeking out. Estee Lauder’s excellent Private Collection, released in 1973, is an American cousin in a deeper shade of green with more flowers. Prada’s more recent hit, Infusion d’Iris owes a debt to No. 19 as well. Chanel’s “updated” flanker, No. 19 Iris Poudre, emphasizes the iris and smooths away the galbanum.

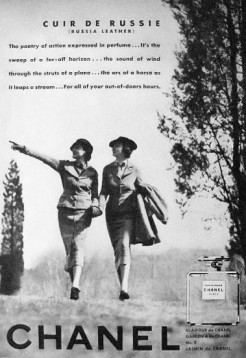

Chanel–Cuir de Russie (1927)

Chanel–Cuir de Russie (1927)

In the pantheon of iconic leather perfumes–Gres’ Cabochard, Robert Piguet’s Bandit, Caron’s Tabac Blond, Balmain’s Jolie Madame, Molinard’s Habanita–only Cuir de Russie is still with us in a recognizable (albeit somewhat softer, slimmer) version of its iconic self. There is a brief whiff of saddle, but no whips here, just fine polished leather and an airy iris heart. If you can find the parfum version, nab it.

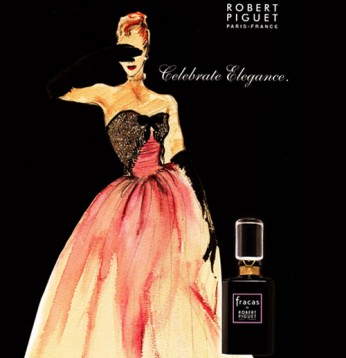

There’s a reason Fracas’ influence can be felt in both Madonna’s Truth or Dare and Lady Gaga’s Fame: she is the original center stage drama queen, a tuberose-orange blossom bombshell in a white satin bias cut dress and an ostrich feather boa. Long may her extravagance reign.

Guerlain–Mitsouko (1919)

Mitsouko is to perfume fans what Chanel No. 5 is to the rest of the world–a classic so iconic that to leave it off this list is unthinkable. It is a golden, autumnal scent–a dusting of dry spices, a refined peach smelling more of warm skin than fruit, and a mossy base. The base suffered as true oak moss disappeared from the perfumer’s palette, but recent reformulations have restored much of Mitsouko’s former glory. The parfum is a much fuller rendition than the eau de toilette. Smell it on your skin, and give it plenty of time to unfold.

Guerlain–Shalimar (1925)

Shalimar’s icy bergamot top, warm floral heart, and smoky vanilla base have inspired dozens of other perfumes over the decades, some of which have become icons themselves (Thierry Mugler’s Angel is wild-child relative), but nothing else has quite the same elegant, feral darkness. Best in eau de parfum and parfum.

Guerlain–Apres L’Ondee (1908)

All those pale, clean florals on the market today wish they could be Apres L’Ondee. The name translates as “after the rain shower” and that is what you get here: flowers rendered in watercolor–violets touched with carnation and anise–and a soft, slightly melancholy cloud of almond-smelling heliotrope. Perfume fans lament its changes over the years and it’s true the vintage parfum is extraordinary, but my newish bottle of the eau de toilette is still lovelier than most of what’s available today. Not bad for 107-years-old.

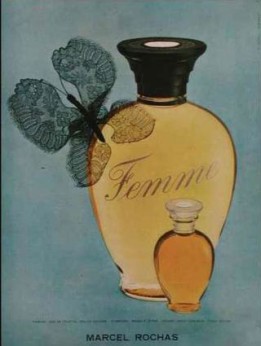

Rochas–Femme (1943)

Full disclosure: Femme is my mother’s signature perfume, but I’m hardly alone in my admiration. The great Edmond Roudnitska, who is perfume’s answer to Shakespeare, created the original in the rubble of war-time Paris using whatever materials he could find. The result smelled of sex, longing and survival—a burst of aldehydes and the darkest of plum hearts wrapped in leather. Femme was reformulated by perfumer Oliver Cresp in 1989 who added peaches and cumin and softened the leather. It is looser, sweeter and brighter than the original but with all its confident sensuality intact.

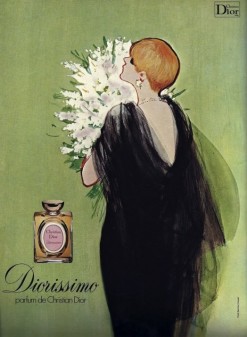

Diorissimo has been reformulated beyond recognition, and by my own rules it should not be here, but I simply cannot leave it off the list. Another Edmond Roudnitska masterpiece, for decades it was the truest, most crystalline rendition of lily of the valley imaginable, until materials crucial to its formula were regulated out of existence. Smell the current version to get a hint of its former greatness, and then try Debut, the lily of the valley perfume Roudnitska’s son, Michael Roudnitska, made for the San Francisco niche line Parfums DelRae.