In Memoriam: Pattern #203, Child Caves

First published in 1977, architect Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language is an odd, ambitious, humorous, deeply humane project rooted in a late 1960’s sense of possibility–the kind of thing it’s hard to imagine anyone attempting now. Alexander and his team spent years researching and observing the ways people most love to live and shelter themselves–the spaces and paths we bend toward even when we’re thwarted along the way. Then they tried to offer these up as replicable pieces or “patterns.” The book moves from macro to micro: a pattern can be large and fairly abstract (“Magic of the City,” “Identifiable Neighborhood,” “Old People Everywhere,”) or very small and specific (“Windows Which Open Wide,” “Seat Spots,” “Pools of Light”). The result is a book that is part manifesto, part practical handbook, part lyric meditation. It is both a dream of a better world and directions on how to build one, a single piece at a time.

All of which makes it a pretty good book to read in a time of heartbreak and despair. I know this because I’ve had it on hand ever since the news broke about Sandy Hook Elementary. I’d pulled it out a few days beforehand, after it came up in the comments section of my post about Everyday Magic. When I started this post I planned to share the final, very beautiful pattern in the book, #253, “Things from Your Life,” which is about the way meaningful objects (rather than fashionable “decor”) can tell our story: “A hunting glove, a blind man’s cane, the collar of a favorite dog, a panel of pressed flowers from the time when we were children…”

But then, like so many other people, I spent a few bewildering days immersed in the news stream and the debates, caught between grief and action, trying to find room for both. And when I returned to the book it opened to another one of my favorite patterns: #203, “Child Caves.”

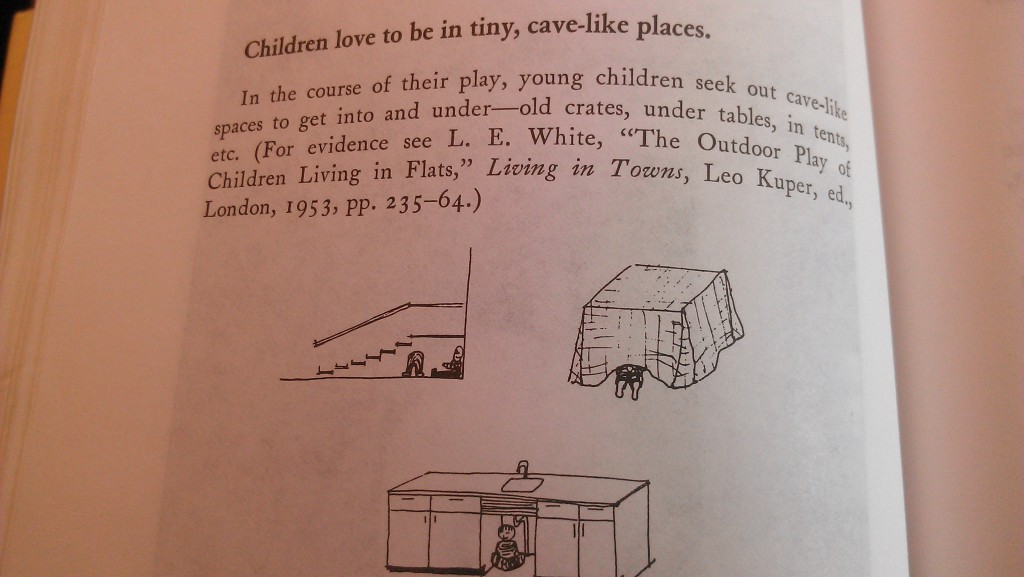

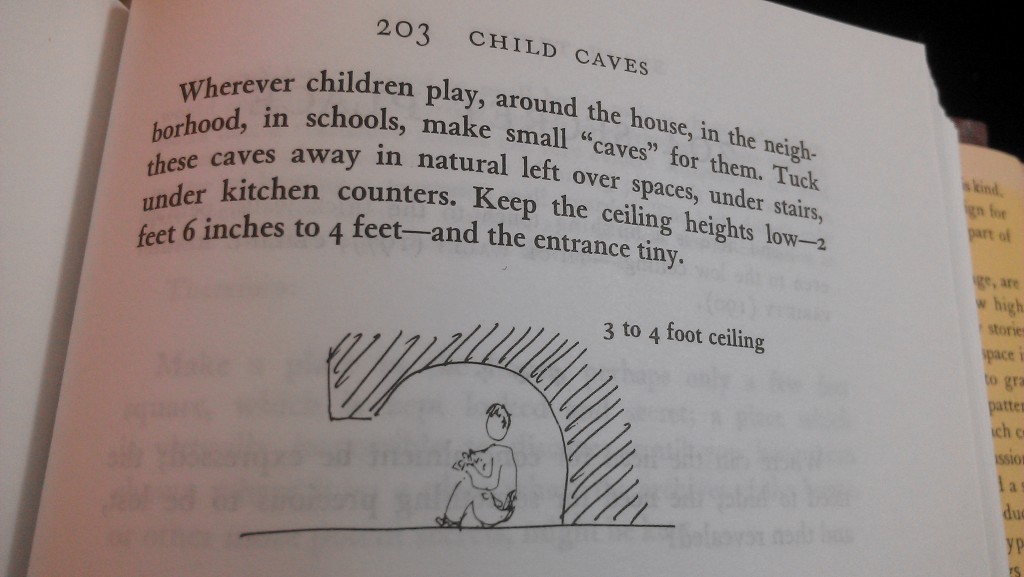

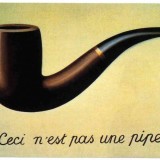

“Children love to be in tiny, cave-like places…” reads the text accompanying the tiny illustrations of a child under the stairs, halfway under a tablecloth covered table, crouched in the cabinet under the sink. “They try to make special places for themselves and for their friends–most of the world about them is “adult space” and they are trying to carve out a place that is kid size.” There follows specific instructions about how many feet of space a child takes up (about five) and how to make a cave big enough for several children because “children like to do this in groups.” “Therefore,” the authors instruct:

I don’t want to say too much about these images. I’ve been writing and deleting all day, looking for the right amount of silence. But I will tell you that I keep returning to them when the clamor surrounding Sandy Hook threatens to overwhelm the silence, the sudden and terrible absence, at its heart. And every time I look again, I’m moved by they way this pattern honors a child’s desire for independence and suggests the need for a safe place to hide. I love, too, the way it asks us to literally carve out a space for children in a grown up world, one adults can only get a glimpse of (“Keep…the entrance tiny.”) no matter how much they might like to follow. We will have to find other ways, piece by slow piece.

Note: If you would like to help the children of Sandy Hook and the residents of Newton, you might look at the list on my Facebook page–it was originally assembled by a Sandy Hook mom. If you’d like to learn more about Christopher Alexander and the effect A Pattern Language had on the world, you can begin here. The book is available for free download here.

12/19/2012 at 10:14 pm

Alyssa,

Thanks so much for sharing this. Over the last few days, I have found myself crying whenever I turn on the TV or look at my computer. This news is just so sad and the timing, just before Christmas, so horrific. I just keep thinking about all those children who are now gone. However, this chapter in the book seems like the most unique tribute – a reminder that we need to honor the children in our lives every day in big and small ways.

I was thinking today about a piece written by a psychologist which says that children feel mostly helpless because they have absolutely no say about what goes on in their lives. Adults pick them up and move them when they don’t like the space the child is in. They make the child eat what the adult feels is right. They monitor each and every second of the child’s life. While this is all in the best interest of the child, it gives the child no say in their own lives. So to create a space that is just theirs, where they have a say over their environment, is such a great honor.

I’m sure my words are inadequate, but I think this was the perfect moment to share this book. I plan to download it and read it immediately. Thanks so much for sharing this with us and for giving us a way to honor those still here and those who are gone.

12/19/2012 at 11:05 pm

Thank you so much, Kandice. I think your thoughts about the piece you read are very wise . Honestly, I almost didn’t put this post up because I feel like my words are pretty inadequate, too. But there was something about those little illustrations that was so moving in this context and needed to be shared… And I’ve read so little about the children themselves, rather than the issues at stake and what is to be done or not done. (All very important too, of course.)

12/20/2012 at 1:01 am

I love that book, and think of it often while walking around cities or town or when inside a particularly well-made house.

As a child, I had a big blue armchair in my room, but I rarely sat in it to read; instead I liked to sit behind it, in the space between the sloping back of the chair and the walls of the corner where it was angled, which was almost enclosed, like a teepee.

It’s strange how small enclosed spaces become uncomfortable, even terrifying as we age, isn’t it?

12/20/2012 at 9:56 am

What a wonderful memory of your blue teepee. I was always wedging myself into small spaces. I supposed I would panic if you put me in a cupboard or a trunk, but I still like nooks, dream of window seats and tree houses, sort of miss my one bedroom second story apartment, and tunnel under the covers… And I remember, at one particularly low point in college, sitting inside a closet and feeling some relief.

A Pattern Language helped me learn to love our Mid-century Modern ranch house–I’d been hoping for a 1930’s bungalow–but showing me all the ways I could make it lean toward my dream home.

12/20/2012 at 10:17 am

I had forgotten how much I used to dream of having a window seat as a kid! Girls on the covers of YA books often seemed to have window seats.

01/01/2013 at 7:20 pm

Oh yes. And I’ve been reading Jane Eyre recently–there’s a great scene near the beginning where she’s hiding in a window seat, one you can actually draw a curtain over. Dreamy.

12/31/2012 at 2:03 pm

Over at the university daycare center (where my daughter goes), they have “quiet boxes” in most of the rooms. They’re big plastic barrels – I guess of the sort you might ship bulk vegetable oil in or something – that they’ve cut doors into and filled with pillows/blankets. A child can go sit in the quiet box if they feel they need it, or it might get suggested to them (“You seem to be having trouble playing nicely with your friends – do you need to sit in the quiet box?). It’s not a time-out and they’re not forced to go there, but they often opt to themselves.

01/01/2013 at 7:22 pm

That’s definitely a child cave! And what a great use for it. I was a solitary child and was always sort of hoping to be sent to my room. It would have been great to have a refuge like that in the middle of a busy classroom.